Driven by geopolitics and economics, the world’s trade routes are seeing a reshift not seen since the ascendancy of “Made in China”. Some analysts such as Peter Zeihan even assert that we are entering an era of “deglobalization”.

As a containership owner, Global Ship Lease (NYSE:GSL) is front and center in this shift in trade patterns. With an estimated annual dividend yield of c.7% and price to book value of 0.63, what are some considerations regarding investing in Global Ship Lease?

The main sources of this report are (i) GSL’s annual reports and management presentations (ii) recent analyst reports on GSL (iii) research reports on broader industry by third parties (Federal Reserve/Congressional institutions etc).

Historical business overview and stock performance

GSL is a containership owner. The business model is simple, GSL buys containerships and leases them out, earning a “charter rate”. If it gets a higher charter rate than its cost for purchasing the ships and opex (including the cost of capital) then it turns a profit; otherwise it turns a loss. This is a very cyclical business, with the gyrations heavily driven by the overall balance between supply and demand for shipping in addition to any Company-specific factors.

This is reflected in GSL’s stock price, which collapsed during the 2008-09 financial crisis, bounced back during the ensuing recovery in 2010-11, and collapsed and stayed low from 2015-2020. Since the COVID-19 lows of nearly $2/share, GSL gained almost tenfold. Is this sustainable, or will we see another reversion to low levels?

GSL stock price (stockcharts.com)

Historical financials

Historical financials per Seeking Alpha are shown below:

The income statement showed very strong earnings in the past 2-3 years, on paper, this seems good (especially if you consider that the $300mm of TTM net income corresponds to a market cap of $722mm).

Table 1: GSL income statement in the past 3 years

| TTM | Dec-22 | Dec-21 | |

| Revenues | 645.9 | 604.5 | 402.5 |

| Cost Of Revenues | -202.6 | -188.6 | -143.4 |

| Operating Expenses (mainly D&A) | -90.8 | -58.7 | -29.4 |

| Net Interest Expenses | -28.6 | -42.7 | -55 |

| Other items | -11.4 | -21.6 | -3.2 |

| Net Income | 312.5 | 292.9 | 171.5 |

| Basic EPS | $8.48 | $7.74 | $4.65 |

Source: Seeking Alpha

GSL has used the proceeds from this windfall to pay down its debt over the past few years.

Table 2: GSL balance sheet in past 3 years

| 23-Sep | Dec-22 | Dec-21 | |

| Total Current Assets | 264 | 237 | 143 |

| Total Assets | 2191 | 2106 | 1994 |

| Total Debt | 862 | 934 | 1071 |

| Net Debt | 720 | 776 | 995 |

| Machinery, Total | 2017 | 1886 | 1878 |

Source: Seeking Alpha

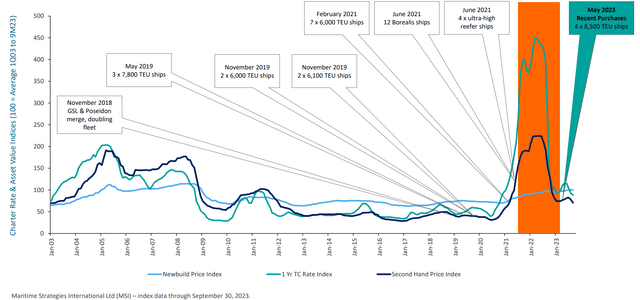

However, this financial performance should be viewed in the context of the surge in charter rates during COVID (due to shipping bottlenecks (i.e. port congestion reducing effective shipping capacity) and an overheating boom when money was “free”). As shown below, the huge surge in charter rates has mostly retreated to pre-COVID levels, so the COVID performance should be viewed as a one-off.

Charter rates (GSL Mgmt presentation)

In fact, it is obvious from the above chart that pre-COVID shipping rates were at low levels for years, or almost a decade. If global shipping rates languish in cyclical troughs as in previous years, GSL could be in a period of low to negative profitability, which would destroy value.

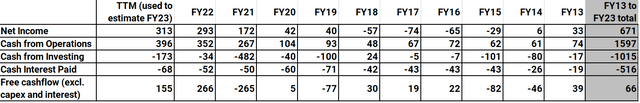

If we take a step back and look at cumulative earnings from FY13 to FY23 (using TTM Sep-23 in lieu of FY23, which should be pretty similar):

GSL profit and cashflow forecast (Seeking Alpha)

Total net income was $671m, but if viewed from a cashflow perspective, $1.6bn in operating cashflow was used for $1bn in investing cashflow and $0.5bn of interest payments, which means over 11 years, shareholders were left with a paltry $66m in free cashflow (excluding capex and interest). The big question is whether the next decade will look more like COVID windfalls or like the decade preceding COVID windfalls (with largely near nil free cash flow).

Future financial forecast:

While GSL states it has 2.1 years of TEU-weighted contract cover as of Sep-23 (profitability of these contracts is not mentioned though FY24 EBITDA is forecast to be at levels similar to FY22 and FY23), once charter rates are renewed at lower levels, given the charter rate chart above, it appears profitability will probably sink back towards something closer to historical levels, driven by short-term supply/demand impacts as well as unfavorable longer-term industry dynamics (see below for more).

Also, GSL cannot distribute all of the windfall, as a large portion of the profits will have to be set aside for replacement capex (as discussed below in the section on capex forecast). Even if GSL achieves similar financial performance and dividend payouts in FY24-25, the investor would be looking at c.7% dividend yield for 2 years and then heightened uncertainty afterward.

Current stock price would appear to price in the potential negative impact from lower rates if charter rates are renewed at lower levels – a recent analyst report from Jeffries (“Quietly Sailing Towards a Record Year”) suggests the stock could only be worth $12.5/share if shipping rates fall back to 2010-2020 average levels (which seems like quite a plausible scenario to me).

1. Short-term supply/demand impacts:

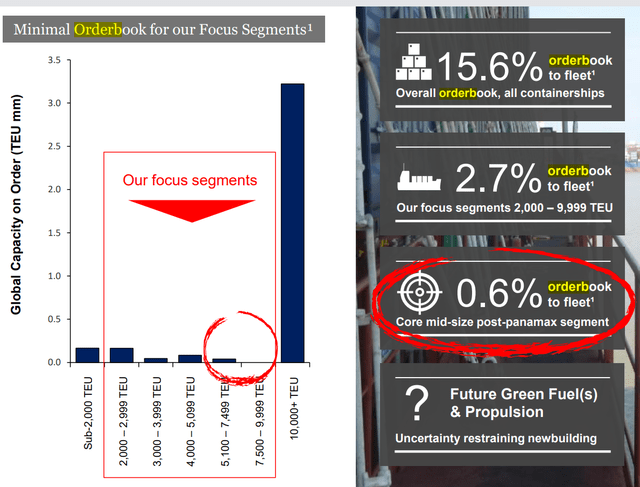

The supply/demand of containerships has also drastically changed. In the 2021Q1 Management presentation, it was highlighted that the containership orderbook to fleet ratio (for the next 3 years) was 15.6% for all ships and 2.7% for their target market.

2021 Q1 orderbook to fleet ratios (2021 Q1 Mgmt presentation)

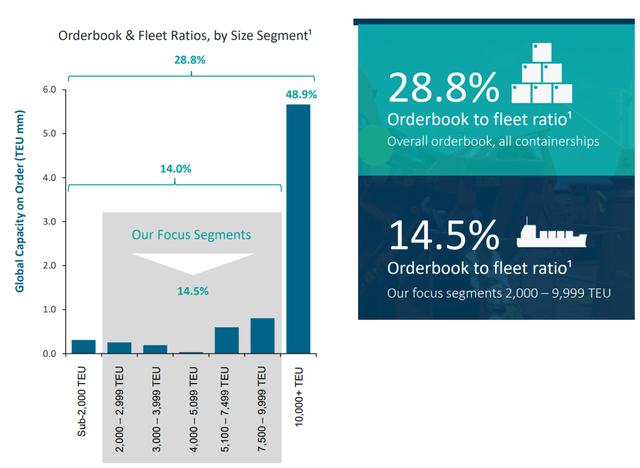

The latest 2023Q3 Management Presentation shows far more supply coming online with an orderbook to fleet ratio of 28.8% (compared to above 15.6%) for all containerships, and the industry consensus that this will massively increase supply for this industry.

2023 Q3 orderbook to fleet ratios (2023 Q3 Mgmt presentation)

Unfavorable long-term industry characteristics:

It seems abnormal for an industry to experience such a long period of glut and still find it hard to balance. A recent congressional report stated that the global shipyard industry has been plagued by overcapacity in past decades. Many countries have heavily subsidized or even bailed out their unprofitable shipyards, and this industry remains unprofitable. For some reason, this industry appears to be perennially unprofitable, with very long periods of unprofitability in its downward cycles.

I would hypothesize that this may be due to several factors:

- Shipping capacity is easy to add but hard to decrease: Ships are easy to add but hard to decommission. Once operational, it makes sense for an owner to keep leasing them out, even if it barely covers costs. With an economic useful life of 30 years, the exit barriers mean basically that any new capacity impacts the supply/demand balance for decades. Every once in a while, there is a boom in shipping demand and rates which leads to a boom in ship supply and then rates revert to normal levels and languish for long periods of time.

- Moreover, shipyards (90% of tonnage produced in East Asia, according to a congressional report) have production capacity that way outstrips demand and can produce at unprofitable prices:

- Shipbuilding is very capital intensive and “scalable” and the East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea) are well known for ploughing capital into making an endless amount of something when they are able to make the first widget competitively (e.g. Japan with memory chips in the 1980s).

- Shipbuilding may also be considered “strategic”, as the same Congressional report above notes, cargo ships transport 90% of the military equipment needed in overseas wars. So these nations are effectively turning a blind eye to the profitability of the shipyards.

- It may also be driven by the fact that these three countries are all big exporters and may want to control their own “means of export” and keep shipping rates low as the big money is in the exports rather than ships.

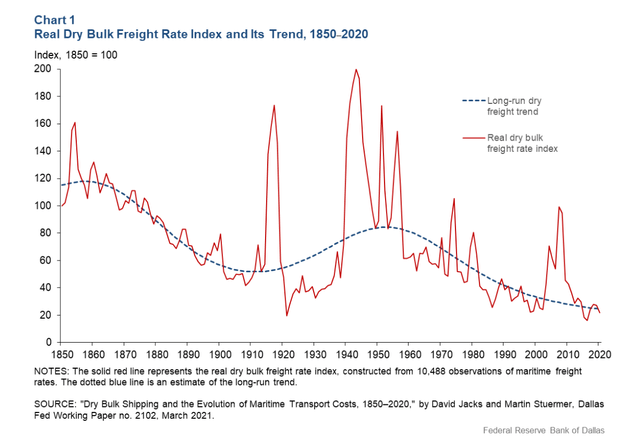

Also, according to a Federal Reserve research report in 2020, shipping rates have mainly been driven by demand booms rather than supply changes. This makes sense as supply is relatively predictable while demand can surge or wane due to unexpected factors. If we look at the history of shipping rates from 1850-2020 (or even post World War II 1950 to 2020), shipping rates booms were usually relatively short-lived and followed by long periods of going nowhere. For example, from 1970 to 2020, we could see several spikes largely followed by long periods of languishing shipping rates. This would suggest that shipping rates are usually around their long-term average (which, if the past decade is any indication, has been quite unprofitable for GSL).

1850-2020 Freight rate index (Federal Reserve)

Whatever the reason, the result is that this is a very difficult industry that has not generated many profits in the past decade (except for the COVID one-off boom); hence I would tend to view this industry with caution until it is very certain that the industry has fundamentally changed (e.g. containership supply does not easily increase to meet or exceed short-term upswings in demand.

Future capex considerations:

One of the biggest concerns I have for GSL is not what’s on the balance sheet, but what’s not on the balance sheet.

As disclosed in the FY22 annual report, as of Dec-22, the TEU weighted average age is 15.9 years (so at Dec-23, this would be roughly 16.9 years).

GSL’s annual report states it assumes that these ships have an average economic life of 30 years, then starting FY24, GSL’s ships have a 13-year useful life until they need to be fully replaced (though in practical terms, the “expiration” of the ships and the replacement capex would be staggered across several years rather than concentrated in one year).

This theoretical abstraction does demonstrate that GSL’s economic value:

- Is heavily dependent on “rolling over” the existing fleet through replacement capex. This is not a business that can just distribute its cashflows – significant amounts will need to be set aside to fund replacement capex. (i.e. the short term capex guidance is not very meaningful – the Company can save on capex for one or two or even several years without meaningful impact on short-term profitability, but at some point the piper will have to be paid).

- Assuming GSLs needs to be replaced in 13 years (at an amount equalling current net book value), that is $1.7bn in 13 years (previous 10 years’ capex investment was $1bn, corresponding to free cashflow of near nil). Even if GSL earns a large windfall in the next year or two from previous contracts, a large portion of it will need to be set aside for replacement capex especially if GSL/the industry is forecasting some lean years ahead.

The wildcard:

The really interesting scenario would be if “deglobalization” fundamentally disrupts the supply/demand balance:

- For example, if supply suddenly contracts because Asian (Chinese, Korean and Japanese produce 90% of the tonnage) shipyards are “unavailable” due to conflicts.

- while demand could overshoot supply (e.g. though overall global demand decreases, it decreases less than the supply impact).

- Then GSL’s ships would be very valuable as charter rates would soar due to constricted supply (that would be projected across years if not decades) but a favorable (or not too unfavorable) demand/supply imbalance.

- Under this scenario, GSL may be an interesting buy, but before then, it appears until there is strong evidence that the containership industry is breaking out of its low profitability mold, I would rather not invest in it.

Overall conclusion:

Though the stock price is trading below NAV and at a relatively high dividend yield of c.7%, I would refrain from buying as:

- Current industry economies do not indicate sustainably strong long-term profitability for this industry, as it still trends towards overcapacity.

- Additionally, current charter rate prices suggest profits may fall in the next several years, which may heavily impact dividends. There is no indication of when the supply/demand balance could be restored to a point where GSL could consistently earn large profits (that can afford 7% dividend yields), which could make the future value of GSL quite volatile.

- However, if there are indications that the supply/demand situation of the industry will structurally and irrevocably change (e.g. access to Asian shipyards is restricted/lost for an unforeseeable number of years), then this might be an interesting stock to snap up.

Read the full article here